21 February 2021

The place of AirSea Battle in strategic thought and its value as a conceptual military doctrine when applied to the Western Pacific, in deterring, and if necessary, fighting the People’s Republic of China in a hypothetical conflict

Originally produced for the University of Exeter Stategy and Security Insitute's MA Applied Security Strategy course

Full paper available as a PDF:

Abstract

This piece seeks to explore the place of and evaluate the effectiveness of the US doctrine known as AirSea Battle (ASB). ASB was conceived as a way of overcoming advanced Anti Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) capabilities that threaten US freedom of movement and deny it the ability to make war as it has done in previous conflicts since 1945. This paper argues in favour of ASB, despite the controversy surrounding it. This piece first looks to what doctrine is and how it is made, and issues specific to naval and air doctrine. This section also looks to maritime theory and more land-centric alternatives in order to understand ASB’s place in wider US strategy and how Chinese behaviour fits into this theoretical framework. It then looks to gain a deeper understanding of ASB and Chinese A2/AD. It defines A2/AD and the debate around the term, before looking at the PRC’s A2/AD capabilities and how Chinese concepts suggest these systems may be utilised. It then explores ASB. Discussed are the assumptions of ASB, the details of the ‘candidate campaign’ envisioned by van Tol. Et al. (and how it relates to later, DoD produced material), and Australian and Japanese views on ASB - the concept assumes the participation of these countries. It then aims to evaluate ASB as a deterrent to the PRC and its potency in a hypothetical conflict with the PRC. Noting how these criteria overlap, this section takes a thematic approach. After introducing the criteria, and some counterarguments and proposed alternatives to ASB, it then addresses both criteria in sections looking at the debates on ASB’s assumptions, around escalation and on resolve and credibility. It will recognise the flaws while still promoting ASB and rejecting its alternatives. The piece then finishes with a summary of the above sections, and concluding remarks suggesting how ASB could be improved to best deter and, if necessary, fight against the PRC.

About the Author

Oliver Boxall holds an MA in Applied Security and Strategy from the University of Exeter, and has previously studied History and Politics at the University of Birmingham. He also has work experience from the defence and construction industry.

1. ASB’s effectiveness in deterring potential PRC aggression against the United States or allies in the region.

2. ASB’s ability to successfully bring a potential conflict between the PRC and the USA to an end state favourable for the latter.

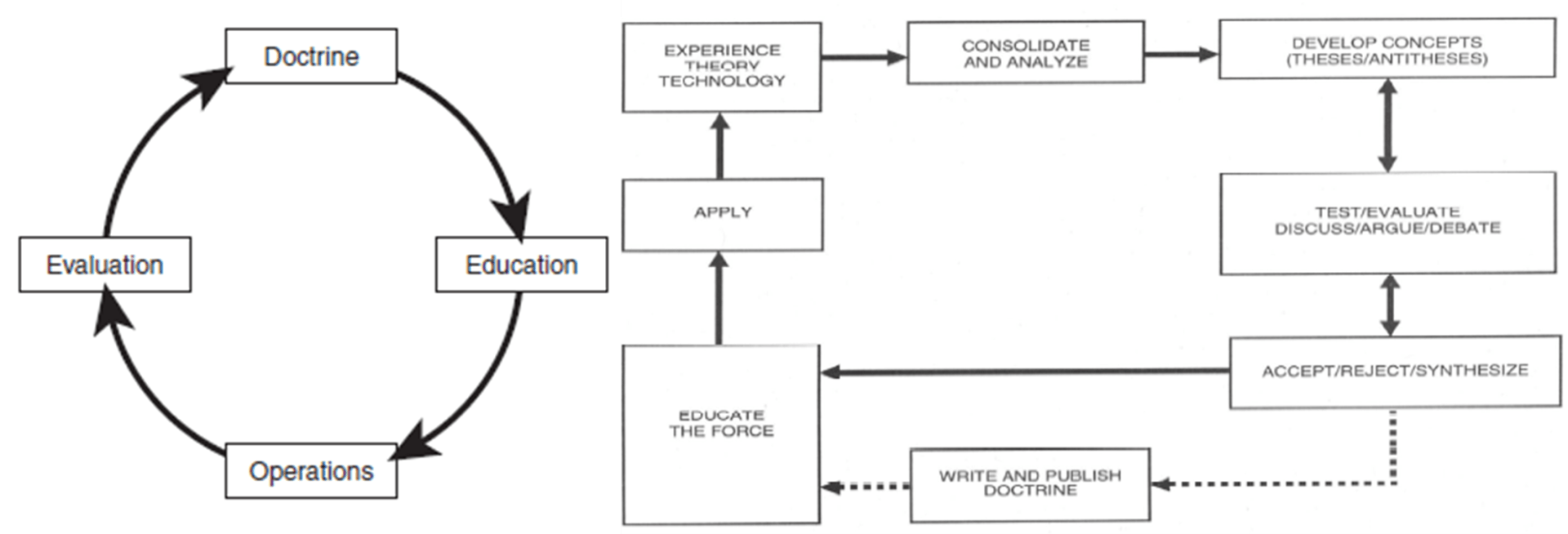

Fig 2: Till’s model of the doctrine process cycle. (Till, 2009, p. 4)

Fig 1: Drew’s model of the doctrine process cycle. (Drew, 1995)

Much writing about doctrine is land centric. There are also issues with making naval and air doctrine worth considering. Naval officers spend a great deal of time honing the technical skills of sailing, and the way navies are organised (ship captains having a great deal of independence and less layers in the chain of command) means that navies often display an indifference to doctrine. (Till, 2009, pp. 39-40) For equivalent reasons, and the fact they are much newer than both navies and armies, Air Forces have also displayed these tendencies. (Brodie, 1955, pp. 350-351) (Mowbray, 1995, pp. 2-4)

Till points to the Naval profession’s hesitancy to embrace formal doctrine over reliance on experience and offensive instinct. (Till, 2009, p. 40) Schmidt argues that in the past, the US Navy preferred to label doctrine as something else, finding the term restrictive – demonstration of this aversion in principle if not in spirit. (Schmidt, 1993, pp. 50-51)

Amongst air forces, there has been similar institutional scepticism of doctrine. Mowbray examines doctrine issues in the USAF. As well as a lack of doctrine process (which prompted Drew’s work); he notes the force has tended to neglect airpower theory in favour of a focus upon technology, to the point that technology and winning procurement battles has driven doctrine. (Drew, 1995, pp. 5-8) (Mowbray, 1995, pp. 3-4, 7) Mowbray also argues that times of perceived failure (such as after the Korean and Vietnam wars) have made the USAF reluctant doctrinally to commit to certain missions to avoid such tarring with failure. (Mowbray, 1995, pp. 6-7,9-10)

Despite the dangers of bad doctrine, and these specific issues with doctrine-making for air and naval forces, it is recognised that modern navies and air forces require a solid base of doctrine in order to carry out operations effectively. Mutual understanding of capability and intent is required in joint operations. (Schmidt, 1993, pp. 53-56) (Mowbray, 1995, p. 13) Till, in his own words and paraphrasing Clausewitz notes that, at sea, the very lack of recent combat along with rapid technological change means doctrine is more important not less in the contemporary world, acting as a handrail for commanders facing uncertain situations. (Till, 2009, pp. 40, 46-47)

Perhaps the best parallel to ASB is its terrestrial predecessor and namesake, AirLand Batte. ALB emerged as a response to the changing balance of power in 1970s Europe. The US had previously relied upon its greater nuclear arsenal to deter the conventionally superior Warsaw Pact. As the Soviet Union gained nuclear parity, the balance in the region shifted away from the US and NATO. (Van Tol, et al., 2010, pp. 5-9)

ALB, a joint Army-Air Force doctrine sought to address this trend. It did so by utilising PGMs, communications technology, and superior aircraft to strike at Pact conventional numerical superiority. Precisions strikes upon bridges, highways, bases and runways in the rear of Pact territory were to be conducted to disrupt and slow the movement of men and materiel westwards; while NATO land forces would utilise a persistent, highly mobile strategic defence (often using small, tactical offences) to slow/stop the advance of Soviet ground forces and deny them the initiative. ALB sought to stop the Warsaw Pact from concentrating its larger forces, depriving them of their main conventional advantage, while fully exploiting NATO advantages and buying space at time for US reinforcements to arrive. (Lock-Pullan, 2005, pp. 681-685) (Long, 1991, pp. 56-64)

The war with the USSR and Pact that ALB was intended to fight never happened, with the cold war ending in 1989-90 and the Soviet Union itself collapsing in December 1991. Some point to this as evidence of ALB’s success in deterring the USSR. While nuclear deterrence was at least as much at play as conventional deterrence in the 1980s, ALB was a clear signal to the USSR that the US would not fight on Soviet terms; and to NATO allies in continental Europe that the US had the technology, willingness and methods to defend their territory. Features of ALB were applied successfully against the Iraqi armed forces in 1991, despite being conceived with central Europe in mind. (Van Tol, et al., 2010, p. xi) (Lock-Pullan, 2005, pp. 692-694) Regardless of whether ALB’s greatest triumph was its role in conventional deterrence vs the Soviet Union or the flexibility that let it be applied to Iraq, it was considered an innovative and successful piece of US doctrine. (Van Tol, et al., 2010, pp. 5-8)

This elaboration of the thought process behind ALB is an example of successful doctrine-making. That ASB is named in deliberate reference to ALB is evidence of a clear desire to replicate said success, in the mainly maritime environment of the WPTO. (Van Tol, et al., 2010, pp. 5-8, 79) Like ALB, it makes use of strengths in one domain, compensating for weaknesses in the other. The JOAC extends this further with cross-domain synergy, allowing greater flexibility and the potential for additive advantage generated in multiple domains to greatly enabling access in another. (Department of Defense, 2012, pp. 14-16) ASB also takes from ALB the idea of asymmetry – both aim to overcome the adversary capability with alternative rather than identical measures and defeat adversary weaknesses with American strengths. (Department of Defense, 2012, pp. 16-17)

Maritime Theory for the US and China

As a maritime power, the US relies upon the mobility of the global commons (the sea, air and increasingly space and cyberspace). (Posen, 2003, pp. 8-15) (Dian, 2016, pp. 240-242) Maritime theory remains dominated by two turn of the (20th) century thinkers, the American Alfred Thayer Mahan and British Julian Corbett. (Gough, 1988) (Till, 2009, p. 48) Both looked at modern and early modern history to understand why maritime powers, especially Great Britain, had risen to pre-eminence on the world stage and to illustrate their theories. (Corbett, 1911) (Mahan, 1890) (Till, 2009, pp. 52,58) The continued prominence of both in the present day suggests that despite technological and social change that there are enduring concepts in maritime strategy. (Till, 2009, pp. 42, 48)

Mahan’s focus was upon securing command of the sea, by attacking enemy commerce or by the destruction of the enemy fleet(s) in decisive battle. He also placed significance on the holding of strong points like ports, isthmuses and straits. (Till, 2009, pp. 52-54) (Mahan, 1890, pp. 3-17, 39-43) Corbett argued that command of the sea was relative rather than absolute, it could be temporary or permanent, and over a large or small area. Due to this, he placed less emphasis upon command of the sea and decisive battle than Mahan and more upon control of lines of communication and of the movement that the sea provides. He pointed to the fact that naval powers could fight a limited war in a way that land powers could not, due to proximity encouraging utilisation of all available forces. This meant a sufficiently strong sea power could fight wars on a scale of their own choosing. (Till, 2009, pp. 56-59, 60-63) (Corbett, 1911, pp. 43-53, 63-69, 75-78) (Bowers, 2018, pp. 47-48)

The thought of Corbett is not opposed to that of Mahan, there is much that the two men saw in common. Both note the importance of the sea for trade, power projection and the utility of the naval blockade. (Gough, 1988, p. 8) (Murphy, 2015, p. 97) Scholars, naval officers and politicians can advocate both Mahanian or Corbettian ideas, although usually, directly or indirectly they do tend to lean one way or the other. Bearing this in mind, the mark of both Mahan and Corbett can be seen upon US maritime strategy of the past few decades. (Till, 2009, pp. 54-56, 67-68) (Murphy, 2015, p. 97)

The Maritime Strategy of the 1980s (developed 81/82, made public in 1986) is a good example. (Brooks, 1986) The Maritime Strategy was the US Navy’s contingency strategy in the event of a conventional war between NATO and the USSR, and despite being a strategy rather than a doctrine it is often considered ALB’s Maritime counterpart. (Murphy, 2015, p. 103) A core focus of the Strategy was on the destruction of the Soviet Navy – pursuit of Mahanian decisive battle, if an asymmetric and unconventional one given the much larger US surface fleet and the Soviet Navy’s reliance upon submarines and land based Maritime Strike aircraft. (Till, 2009, p. 55) (Brooks, 1986, pp. 66-67) However, the strategy also sought to put pressure on the Warsaw Pact’s periphery, blunting any potential thrusts into Norway or Turkey and striking at Soviet forces in the USSR itself. This latter element rather more in the vein of Corbett than Mahan. This is reinforced by the Strategy’s intent to demonstrate to the USSR that the US would be willing to fight a protracted and truly global conflict with calls for Naval power to be applied against the Russian far east and distant Soviet clients like Cuba and Vietnam if necessary. (Brooks, 1986, pp. 66, 79-82 86-88)

Murphy argues the predominant theorist guiding US Navy Strategy since 1945 has been Corbett. (Murphy, 2015, p. 97) Till’s argument is similar, noting the Corbett-esque philosophy behind ‘Naval Doctrine From the Sea…’ and ‘Forward, From the Sea…’; two important doctrine publications of the 1990s. (Till, 2009, pp. 67-68) This does not mean that the Mahan’s theories and ideals were ignored in this time (we can see elements of his thought in The Maritime Strategy), but Corbett’s ideas bore greater influence. Indeed, Murphy suggests there was a brief swing back towards Mahan and decisive naval battle in the 1970s as the Soviet Navy expanded rapidly. (Murphy, 2015, p. 103) Till notes this tendency too, observing that the Soviet Navy at this time also had a similar approach. (Till, 2009, pp. 54-55) Corbett’s ascendency over his American counterpart is more de facto than de jure. The USN publicly grants greater prominence to Mahan, perhaps unsurprisingly given his service in that institution. However, actual thinking, planning and fighting has generally been more Corbett-esque. (Murphy, 2015, p. 97)

ASB seems a part of this tradition, bearing the mark of Mahan and Corbett but more of the latter. There is little of seeking of decisive naval battle, and a recognition that A2/AD deprives the US of local command of the sea. (Van Tol, et al., 2010, pp. 52-75) (Department of Defense, 2012, pp. 2, 4-10) It proposes a novel way to regain this command of the sea (and the rest of the commons) to allow a distant blockade and follow-on operations to bring a conflict to favourable conclusionThe geography, history and culture of China differ drastically to that of the US. That the author of this piece is a British scholar with no knowledge of the Chinese language is recognised as a significant limitation of this piece. This work will thus rely on interpreting Chinese policy and strategy as manifested in the real world (as opposed to trying to get inside the military-political psyche of the CCP), as well as the works of other scholars. – aspects identified by Corbett as being enabled by command of the sea. (Corbett, 1911, pp. 118-121) (Prescott, 2016)

The geography, history and culture of China differ drastically to that of the US. That the author of this piece is a British scholar with no knowledge of the Chinese language is recognised as a significant limitation of this piece. This work will thus rely on interpreting Chinese policy and strategy as manifested in the real world (as opposed to trying to get inside the military-political psyche of the CCP), as well as the works of other scholars.

In stark contrast with western militaries, the PLA is inherently politicised, it originated as, and is still de jure the Army of not just the Chinese state but the CCP. (Defence Intelligence Agency, 2019, p. 16) However, scholars note that the influence of Communist/Maoist thought upon Chinese strategy making is less significant than those of Chinese history (Confucianism and the thought of Sun Tzu) on the one hand and realpolitik (sometimes referred to as the parabellum culture) on the other. (Feng & He, 2019, pp. 4-5) (Ghiselli, 2018, pp. 171-177) This traditional thought, particularly Confucianism, is generally risk averse and stability focused, seeing war as a last resort. The parabellum/realist tendency is more aggressive, seeking relative gains and being more open to opportunistic use of force; and is more significant, especially at times of perceived tension on threat. (Feng & He, 2019, pp. 15-16)

The DIA notes a move away from the Army dominated PLA of the past towards a more balanced force, but this is not to be overestimated – 80% of PLA personnel are in the Ground Forces. (Defence Intelligence Agency, 2019, pp. 3-6) (Jinn, 2004, p. 19) China may have a growing Navy and Air Force, but it has historically not been a maritime power. (Reeve, 2000, pp. 9-10) Thus, Chinese interpretations of theory as manifested on the ground are not those of Mahan or (most of) Corbett, but of land-centric Geopolitics in the tradition of Mackinder, and a navy informed by concepts of the fleet-in-being and the Jeune Ecole. (Røksund, 2007, pp. 1-23) (Till, 2009, p. 70) (Corbett, 1911, pp. 121, 151-163) (Lukin, 2015, pp. 1-4)

Mackinder’s work is outdated in some parts, particularly his focus upon eastern Europe as the ‘geographical pivot of history’. (Mackinder, 1904, pp. 423-429) His appreciation of the vast resources of Africa-Eurasia (‘the world island’) remains relevant, as does his recognition that technology (railways, and after his time, motorways) made rapid, mass movement by land possible. China is the world’s most populous country, 3rd largest in land area and has vast resources at its disposal. This gives it considerable potential to become the preponderant power of the ‘world island’. The PRC seems to recognise this – with the BRI aimed to move trade away from the American commanded commons to Chinese controlled and influenced land. (Lukin, 2015, pp. 1-4) (Mackinder, 1904, p. 437) (Dodds & Sidaway, 2004, p. 294)

Other important concepts are that of the fleet-in-being and the Jeune Ecole. The former essentially involves keeping a potent fleet in place, maintained and supplied as a threat to the other side. It may conduct small raids or attacks, but not risk a major engagement with the opposing fleet. For Corbett, and Hattendorf, the fleet-in-being is a defensive strategy, pursued by a weaker/disadvantaged side to dispute command of the sea. (Hattendorf, 2014, pp. 45-47) (Corbett, 1911, pp. 121, 151-163) A stronger force (such as the US Navy) can take the offensive to secure and exercise command, by blockade or engagement and by attacking/defending commerce and supporting land operations respectively. (Corbett, 1911, pp. 120-121, 122-136, 187-188, 202-206) The ASBM/ASCM component of Chinese A2/AD has a similar effect to a fleet-in-being in that it is a potent but relatively secure (from naval forces at least) threat, only an asymmetric one. (Jinn, 2004, pp. 16-18) (Biddle & Oelrich, 2016, p. 12)

The Jeune Ecole (French for new school) was connived by the French Navy in the 1870s onwards. France had to cut its Navy due to the land threat of Germany at this time. Notable for the employment of asymmetry at sea, the Jeune Ecole sought to use new technologies (steam power and the torpedo) to arm small boats to strike at much more powerful but vulnerable battleships of an adversary. Like the fleet-in-being, it is a strategy of the weak, but still potentially dangerous. The submarine renewed interest in the Jeune Ecole. (Till, 2009, pp. 68-74) (Røksund, 2007, pp. ix-xiv, 225-229) China’s short ranged but quiet conventional attack submarines, as well as the anti-air and anti-ship aspects of its A2/AD follow the same logic – targeting large surface warships with many smaller, cheaper, and more numerous platforms.

ASB is a doctrine that seeks to overcome an adversary’s (primarily China) ability to deny the US command of the commons. Restoring this command then allows successive operations to achieve the mission and end a conflict. (Van Tol, et al., 2010, pp. 53 ,75-79) (Department of Defense, 2012, pp. 1, 16-18) Understanding the theoretical concepts that underpin doctrine and strategy is essential to assessing their utility without resorting to exercises or observation of a war. (Till, 2009, pp. 40-42)

AirSea Battle and Anti Access/Area Denial

This section will examine in detail the PRC’s A2/AD capability and A2/AD in order to subsequently assess ASB in the following section.

The A2/AD Debate

Anti-Access and Area Denial are separate but related concepts, with similar systems that enable them. The difference is one of range and scale. Anti-Access systems restrict, slow or block movement to a theatre, whereas Area Denial systems do the same but within a theatre. (Krepinevich, et al., 2003, pp. 3-5)

Anti-Access and Area Denial are not new concepts. It makes sense to keep enemy forces away from certain areas, especially those near one’s own centre(s) of gravity (the capital, population centres, bases or likely sites of battle or enemy objectives. (Kearn, 2013, p. 134) (Davin, 2013, pp. 3-5) As alluded to in the theory section, the Fleet-in-Being and Jeune Ecole are essentially A2/AD strategies, keeping enemy forces away from one’s coastline by posing a significant threat if they venture too close.

However, in recent decades, the range, lethality and interconnectedness of systems enabling A2/AD have dramatically increased, and the technology has proliferated geographically. When scholars refer to A2/AD it is usually this current manifestation, consisting of integrated air defence systems (IADS), long range radar, stealthy conventional submarines, modern sea mines, and long-range anti-ship cruise and ballistic missiles (ASCM/ASBMs). Offensive cyber and space capabilities (those that destroy or degrade networks, communications and satellites) are also sometimes included within A2/AD, in that these prevent ‘manoeuvre’ (transmission of information) in space and cyberspace, which also form part of the commons. (Cliff, et al., 2007, pp. 44, 51-80) (Dobbins, et al., 2017, pp. 8-10) (Kearn, 2013, pp. 133-136) With the range of modern weapons, A2/AD can cover considerable distances, out into international waters and airspace, and thus deny local command of the commons. (Davin, 2013, pp. 5-6) (Department of Defense, 2012)

A2/AD is sometimes labelled as a doctrine or strategy, or even a ‘new way of war’. Davin points out that these are inaccurate claims to make about a common-sense concept that has existed long before the advent of the aeroplane, ballistic missile or computer. (Kearn, 2013, p. 134) (Davin, 2013, pp. 3-5, 18) However, the technology and range of A2/AD systems like those possessed by the PRC do necessitate new approaches to counter them at the tactical and operational level. (Department of Defense, 2012, pp. 9-11)

Thus, it is important to distinguish between A2/AD as a collection of capabilities (as described above) and what some unhelpfully label as an ‘A2/AD strategy’. (Bitzinger, 2016, pp. 2,11) (Kearn, 2013, pp. 134-136) The latter is a poor and confusing term. Still, it can be summed up as the utilisation of A2/AD to fight on the strategic defensive but tactical and operational offensive, reliant upon attrition and inflicting unacceptable losses upon a materially superior foe. (Defence Intelligence Agency, 2019, pp. 23-24) (Davis, 2016, pp. 430-431)

Chinese A2/AD

It is important to recognise that A2/AD is a western label and not used in China. The PRC instead uses concepts of ‘Active Defence’ and the ‘Shashoujian’ (assassins’ mace) to describe how it intends to utilise A2/AD capabilities in a way consistent with what some westerners have labelled an ‘A2/AD Strategy’. (Davis, 2016, p. 430) (Krepinevich, 2010, pp. 13-15)

Biddle and Oelrich provide a highly technical and detailed analysis of A2/AD capabilities. The IADS and Anti-Ship missiles have range limitations based upon their reliance upon radar of around 400-600km. (Biddle & Oelrich, 2016, pp. 13, 28-29, 33) Jinn notes the vast PLA cannot afford to modernise completely, and thus instead focuses upon ‘pockets of excellence’ to asymmetrically counter US and allied forces. (Jinn, 2004, pp. 12-18) In this way, the PLA seeks to use ‘inferiority to beat superiority’ through the use of ASAT, offensive cyber and ballistic missiles – the latter of which outrange US countermeasures. (Davin, 2013, pp. 12-13) (Davis, 2016, pp. 436-441)

Active defence is China’s declared military strategy to win a ‘local war in informationised conditions’ – the Chinese term for Network-centric warfare and multi domain operations encompassing space and cyberspace. Davis describes it as operationally and tactically offensive and strategically defensive. Davis’s interpretation of Peng and Yao, along with Dobbins suggest that pre-emptive strikes are consistent with this concept of defence, for example, in response to US Navy Freedom of Navigation (FONOPS) or a hypothetical Taiwanese UDI. This is consistent with the initial Chinese attack imagined by van Tol’s team in the ASB concept. (Davis, 2016, pp. 430-434) (Feng & He, 2019) (Van Tol, et al., 2010, pp. 20-23, 53-56) (Dobbins, 2012, pp. 4, 10)

The Shashoujian is a vaguer concept. Brudzinski’s analysis of numerous PRC sources suggests it hinges upon capabilities required to win a high-tech war or weapons with ‘an enormous terrifying effect on an enemy’. Cruise and Ballistic missiles are singled out repeatedly. (Brudzinski, 2004, pp. 315-16, 342-344) Moore looks at the ASAT element of Shashoujian and awareness in China and the US at the degree to which the US relies upon satellites for its C2. (Moore, 2014, pp. 164, 176-177) Guha suggests the term is used to describe ‘game changing’ weapons, but also the concept of a ‘decisive thrust’. He also considers ASBM and ASAT weapons as examples. (Guha, 2019, pp. 40-42, 44-47) Regardless of the confusion around the term, it is clear Shashoujian is used to describe many weapons falling under the western A2/AD label and their use in a decisive or war-winning manner.

China has a sophisticated and extensive A2/AD network as understood by the West, capable of denying the US to fight in what has become its standard/expected way since 1945: freedom of movement in the commons, safe ‘sanctuary’ staging areas, reliance upon carriers and other surface ships and air superiority/supremacy. (Van Tol, et al., 2010) Concepts of active defence and Shashoujian demonstrate these systems are clearly directed at the United States’ ability to move forces to the area and support an ally such as Japan or Taiwan. (Dobbins, et al., 2017) (Kearn, 2013) To win an ‘informationised local war’, the PRC has developed systems and doctrines that challenge the US asymmetrically and allow it to impose costs and dispute local command of the commons from an overall position of weakness.

ABS in Depth

The United States has not been blind to its reliance upon access to the global commons to project military force around the globe; or the potential that rivals may realise this and attempt to exploit this weakness. In 2003 Andrew Krepinevich produced a CSBA report on the emerging challenge of A2/AD. This report identified emerging A2/AD capabilities and recognised their threat to American strategic mobility. (Krepinevich, et al., 2003, pp. i-11) Given Krepinevich’s position as an author of the initial ASB concept, this report can be considered to have begun the impetus for overcoming the A2/AD problem. Posen (also in 2003) pointed to the emergence of a contested zone – littoral waters, urban terrain and airspace below 15,000 ft. In this zone, US forces were challenged despite qualitative superiority, and faced losses within it against North Vietnam, Iraq and Serbia. (Posen, 2003, pp. 7, 19-27, 33-38) The PRC’s A2/AD systems create a large contested zone in and over the seas of the WPTO (Biddle & Oelrich, 2016, pp. 11-13)

To this date, the most detailed articulations of ASB remains the CSBA’s 2010 AirSea Batte: A point of departure operational concept, edited by Van Tol; alongside companion piece Why AirSea Battle? by Krepinevich. ASB was made official doctrine in 2012 with its public endorsement by the then CNO Greenert and CSAF Schwarz. (Greenert & Schwartz, 2012) This adoption and endorsement saw the beginning of debate around ASB, including criticism. 2012 also saw the publication of the JOAC, which sits above the ASB concept and is far vaguer, despite essentially rearticulating the need for access to the commons, the challenge of A2/AD and the need to overcome It. The JOAC places great emphasis upon jointness between all forces and introduces the concept of Cross-Domain Synergy which it places at its centre. Cross Domain Synergy is described as the ‘additive employment of capabilities in different domains such that each enhances the effectiveness… of the others—to establish superiority in some combination of domains that will provide the freedom of action required’. (Department of Defense, 2012, pp. 14-17) JAM-GC was introduced in 2015 as an ‘evolved replacement’ to ASB. JAM-GC’s significant difference from the original ASB concept is its consideration of only extant technologies and capabilities rather than emerging or theorised ones. It also expresses some concerns about directly overcoming A2/AD systems, claiming that their effectiveness has increased to the point this may not be viable in certain situations. (Hutchens, et al., 2017, pp. 4-5) This may be partly the case, but it is worth also considering that this may also be included as a PR ploy to avoid the considerable controversy associated with the initial ASB concept. (Etzioni, 2014, pp. 581-583)

Although the original ASB concept recognises the significance of other domains (land, space and cyberspace) in overcoming A2/AD and in any future near-peer conflict; the newer, less known and less discussed JOAC and JAM-GC place a greater emphasis upon them, aiming to prompt the realisation of cross domain synergy and a truly joint-force response to the challenge of A2/AD. (Department of Defense, 2012, pp. 14-17) This is not to say that they downplay the significance of maritime and air operations, which will still figure heavily in any conflict, especially one in the WPTO – given its geography and the great distances involved from the China seas and Chinese coast and the US bases in the area. (Van Tol, et al., 2010, pp. 11-14)

The JOAC and JAM-GC are more generic, lacking the focus upon China as an adversary and the WPTO as a theatre. However, it could be argued this is primarily diplomatically motivated due to the controversy ASB’s obvious focus on China caused. Substance wise, they draw extensively upon the original ASB concept, this history cannot be ignored. Likewise, the broader strategic context of the US as a declining hegemon and its ‘pivot’ towards Asia and increasing rivalry with the PRC must be considered. (Dian, 2016, pp. 237-240, 245-247) Reinforcing this point that the focus upon China remains is the fact that the debate on ASB is almost entirely set around this Chinese context. While ASB may be applied against other adversaries, this debate remains focused upon the PRC; much as its spiritual predecessor ALB was utilised against Ba’athist Iraq but conceived and discussed with the USSR squarely in mind. (Lock-Pullan, 2005, pp. 695-696)

The Candidate Campaign

The Air Sea Battle Concept lays out in extensive detail what it calls a candidate ASB campaign. Said campaign is not tailored to any specific scenario, such as a Chinese attempt to invade/coerce Taiwan, or seize the (disputed, Japanese controlled) Senkaku islands, but rather how ASB would be applied in the case of a major US-China war. Before summarising this campaign, it is worth looking at the assumptions Van Tol’s team make regarding such a conflict. (Van Tol, et al., 2010, p. 10)

They assume the following:

- China as the initiator of hostilities.

- Nuclear deterrence holds. This is stated explicitly by van Tol. Due to its potential consequences, this assumption has attracted significant criticism.

- Active participation of Japan and Australia.

- No ‘sanctuary’ territory. ASB calls for numerous strikes on Chinese territory. Implicitly, Chinese strikes on US territory (notably Guam) would be considered ‘fair game’.

- Contestation of Space.

- A protracted war favours the United States. Due to its advantage at sea, the US could damage China’s maritime trade and thus its economy, while remaining relatively unscathed itself in comparison. Implicitly, this means a short war favours the PRC, and that it would seek to impose costs so great that the US leadership and/or population would seek to end the conflict on PRC terms.

(Van Tol, et al., 2010, pp. 50-52)

The Candidate ASB Campaign envisions an early stage and a follow-on stage, each with multiple lines of operation. The order is not prescriptive, they will run concurrently and for different amounts of time, and aspects of the follow-on stage may begin while the initial stage is still underway.

In brief, the initial stage involves the following:

1. Resisting the initial PRC attack. Numerous methods to do so are discussed, including hardening, concealment, dispersion and active defence of bases. Andersen AFB in Guam, the main hub between Hawaii and the WPTO, is highlighted as being particularly vulnerable.

2. A ‘blinding attack’ upon PRC C2 infrastructure and radar while also preserving one’s own C2, ISR, and infrastructure from adversary efforts to do the same. Van Tol and Kripinevich refer to this as the ‘scouting battle’.

3. Suppression of the PRC’s missile capability (anti-air and anti-ship) with long range strikes delivered from, sea, submarine and stealth aircraft platforms.

4. Seizure and sustainment of the initiative.

The follow-on stage is broken down these lines of operation. As the future cannot be predicted and van Tol et. al. elect not to imagine a specific scenario for their candidate campaign, the follow-on stage is described in much less detail.

1. Continually exploiting the initiative in a protracted campaign.

2. Conducting a distant blockade of the PRC.

3. Sustaining logistics. Given the distances from the theatre for the US this is crucial in any effort, especially a protracted one.

4. Ramping up military-industrial production, especially of PGMs. The US munitions arsenal is already under some strain from limited operations in the middle east. A conflict with China would see stocks deplete rapidly.

(Van Tol, et al., 2010, pp. 52-79) (Mehta, 2018)

ABS for Australia and Japan

The United States has numerous allies in the Region. ASB however, assumes only the participation of Australia and Japan. Van Tol reasons these countries' interests in the WPTO are aligned with the US to the degree they would support their ally in the event of a US/China conflict. (Van Tol, et al., 2010, p. 51) A dispute with Japan over maritime borders or the Senkaku islands may well be the casus belli for such a conflict. (Dobbins, et al., 2017, p. 7) Scholars from these states seem broadly in support of ASB, with some caveats. (Schreer, 2013, pp. 36-38) (Takahashi, 2012, pp. 1-2, 9) (Matsumura, 2014, pp. 24-26, 49-53)

A major implication of ASB for Australia and Japan is that their assumed participation means they may become more likely targets of any Chinese attack, particularly Japan, given its much closer proximity to China, and resident US bases within range of some PLA missiles. (Van Tol, et al., 2010, pp. 19-20) Despite its constitutional limitations on defense spending, Japan has a formidable navy and air force, and arguably possesses ‘regional command of the commons’. While constitutionally it may not be able to partake in offensive action, it would be able to put up a formidable defence of its airspace and coast and support the US with niche capabilities such as minehunting. Its constitutional limits may be removed or relaxed given Japan’s tendency to stretch them as far as possible, and the current government’s increase in spending above 1% of GDP. (Ritter, 2005, pp. 239-248, 257-258) (Wexler, 2020, pp. 45-46) US bases in Japan provide an alternative to Andersen AFB in Guam and carriers to launch strikes in the Scouting Battle and Suppression stages of ASB. Japan's importance is clear – without the assistance of its forces, strategic depth provided by its territory, and established bases, an ASB campaign would be far more difficult to conduct. Van Tol suggests that China forcing Japan out of a war could be the kind of fait acompli that would force the US to make peace on unfavourable terms. (Van Tol, et al., 2010, pp. 19-23)

While a less powerful and more distant (from the WPTO) country than Japan, Australia could still contribute to ASB. The RAAF and RAN, while of limited size, are high-tech, well trained forces with similar cultures and plenty of experience working alongside their American counterparts. Australia also provides great strategic depth and the potential for further dispersion of air forces. Schreer notes the debate in the country regarding ASB, from high enthusiasm arguing for active RAAF participation in an ASB campaign; to rejection of ASB for making Australia a potential target of aggression. (Schreer, 2013, pp. 31-36)

Japan and Australia are capable allies of the US. Schreer and Takahasi, independently of each other, both propose greater incorporation of Australia and Japan into implementing ASB/JAM-GC. Takahashi calls this ‘allied ASB’. This seems an eminently sensible move that may ease the concerns of ASB sceptics in Australia and Japan. (Schreer, 2013, p. 38) (Takahashi, 2012, pp. 1-9)

Evaluating ASB

This section will look to evaluate ASB and ultimately make the argument in its favour. As previously stated, it will first lay out the criteria used for this assessment, before introducing the arguments opposing ASB and the proposed alternatives to it – Offshore Control and Deterrence by Denial. It will also introduce the concept of War-At-Sea, proposed as a complement to ASB. The rest of this section will consist of ASB's actual evaluation against our criteria below in three key areas of critique.

- ASB makes a war with China more likely/inevitable.

- Criticism of ASB as escalatory and its assumption that nuclear deterrence holds.

- Concerns around the credibility of ASB related to signalling and resolve.

Criteria

As stated in the introduction, this section will evaluate ASB against the following two criteria.

1. ASB’s effectiveness in deterring potential PRC aggression against the United States or allies in the region.

2. ASB’s ability to successfully bring a potential conflict between the PRC and the USA to an end state favourable for the latter.

These are both largely if not entirely qualitative matters. Regarding deterrence, ASB makes numerous claims that it preserves the ‘stable military balance’ in the western Pacific. Testing if this claim is true will form part of the assessment as to whether ASB is an effective deterrent, in general and when compared to alternatives. (Van Tol, et al., 2010, pp. 1, 5, 9, 17)

In addressing the second criteria, any analysis done by this paper will be heavily based upon conjecture, as are the sources it draws upon. This is, of course, a significant limitation, but an unavoidable one given the lack of anything resembling a conflict or war between two peer or near-peer adversaries since the Falklands War of 1982, hence the need for a degree of reliance upon conjecture and theory rather than just drawing on real world experience. (Drew, 1995, p. 3)

This paper has opted to investigate these 2 crucial questions in detail rather than a broader scope of criteria with less analysis dedicated to each. Notably, the financial cost of ASB is left out of discussion, even though some critics attack ASB as being too expensive. However, these concerns have been partially rectified with JAM-GC’s focus on extant technology. Additionally, multiple analyses suggest ASB is affordable (albeit barely) if rough US defence spending trends continue. Matsumura’s approach looks at four different spending scenarios, though all represent cuts to the overall US defence budget. In all but the lowest funding scenario is ASB undeliverable, although it is extremely hampered in the second lowest. Matsumura assumes the second highest spend to be most realistic and argues that in this scenario, ASB is at least achievable in the short term. (Matsumura, 2014, pp. 39-41, 49-56) Schreer also makes a convincing case for the US being able to afford implementing ASB. (Schreer, 2013, pp. 14-16) It should be noted that Matsumura and Schreer are Japanese/German-Australian respectively and conditional supporters of ASB, writing about the implications of the doctrine for their countries. There is little motive for either to argue disingenuously about ASB’s affordability in the way there may be for strong American supporters of ASB, (especially those with close links to governments), or opponents of ASB.

ABS's Counterarguments and Alternatives

Opposition to ASB has fallen upon many elements of the doctrine. The 2010 report and its detailed ‘candidate campaign’ against China alarmed many scholars and commentators. Opposition was often centred around the assumptions made by Van Tol’s team, the risks of escalation posed by numerous strikes on the Chinese mainland, and the issues with signalling.

Some critics of ASB have taken it upon themselves to detail alternative concepts for deterring and fighting an adversary with an advanced A2/AD network such as China. The two main alternatives are known as Offshore Control (OfC) and Deterrence by Denial (DbD). (Hammes, 2012, pp. 10-14) (Erickson, 2013) (Torsvoll, 2015, pp. 44, 48) (Kearn, 2013, pp. 143-145) The latter is not to be confused with the broader and more abstract concept of deterrence by denial in deterrence theory. As an alternative to ASB, it will always be referred to capitalised or as DbD.

Offshore Control was conceived by T.X. Hammes. Piefer is another notable backer, although he neglects to use the exact term. Offshore control seeks to deal with A2/AD by simply avoiding it (the offshore element). It is essentially the imposition of a distant blockade, taking advantage of the US command of the commons beyond the range of A2/AD to interdict civilian shipping bound for an adversary and achieve conflict termination through economic strangulation, without putting costly assets in the way of potential harm. By contrast, the American economy, though disrupted of trade with China and suffering costs of a war, would be relatively unharmed, able to trade with the rest of the world at will thanks to its command of the commons. (Hammes, 2012, pp. 10-14) (Peifer, 2011, pp. 125-127,130)

Against the PRC, Offshore control could take advantage of the natural bottlenecks of China’s global trade passes that are the straits of Malacca. This would allow for an effective blockade given the relatively small area of ocean required to be patrolled. (Peifer, 2011, pp. 115, 122) (Mirski, 2013, pp. 404-405) Piefer argues a blockade would be strategically feasible and effectively degrade the Chinese economy. (Peifer, 2011) Mirski agrees but argues that China would be able to fuel a war economy for a significant time on domestic production, and thus it would have little effect initially. An American blockade of China would have vast consequences for the global economy. The US would need the consent of Japan given its importance as an ally. Mirski thus argues many states (notably Russia and India) would likely turn against the US and that China could utilise diplomacy to try and end the blockade as states grew unsatisfied with it. (Mirski, 2013, pp. 410-416) Collins is even more sceptical in his discussion of an oil blockade against China. He highlights the difficulties in discriminating PRC-bound shipping, potential for domestic US objections and China’s significant domestic oil production, land-based imports and range of demand side measures it could utilise in the medium term. He calls the uncertainty that would be generated by knock on effects (of blockade) a ‘pandora’s box… of adverse consequences’ in his argument that a blockade is not a strategy or substitute for one, as is effectively the case in OSC. (Collins, 2018, pp. 59-68, 73)

Offshore control is of dubious deterrent value. Blockades are slow, and a PRC willing to go to war may take gamble upon achieving a quick victory if it thought a blockade would be the likely response. It also leaves allies to fend for themselves. OfC has questionable termination value. Blockades have a mixed record, with successes typically only occurring alongside other military action and many years. A blockade alone would also be unlikely to reverse any Chinese gains or impose significant military costs upon the PRC that might encourage termination. (Collins, 2018, pp. 68, 72-73) (Kearn, 2013, pp. 143-144)

The OFC advocates suggest it as an alternative to ASB suggests that their understanding of ASB is poor, given ASB includes a distant blockade. (Van Tol, et al., 2010, pp. 32, 53, 75) Torsvoll notes the compatibility of ASB and OFC, and Mirski argues strikes on the Chinese mainland would enhance the effectiveness of a blockade. (Mirski, 2013, p. 417) (Torsvoll, 2015, pp. 55-56)

Deterrence by Denial is the second alternative. Initially proposed by Erickson in testimony for the House Armed Services Committee, it rejects AirSea Battle (if not directly or in name) and distant blockade/OfC. It instead seeks to deter China through American investment in A2/AD capabilities of its own in the WTPO, that would deter Chinese military action through the threat of damage or destruction. (Erickson, 2013) (Gallagher, 2019, pp. 34, 39-41) As Biddle and Oelrich note, most A2/AD technology is not exclusive to China and the US and allies could quite easily deploy their own to theatre. (Biddle & Oelrich, 2016, p. 45) In DbD’s favour it is its relatively low cost, and is supported in the fact that many of China’s neighbours possess their own A2/AD networks. Beckley argues in such a conflict, that US assistance could tip the balance in favour of the attacked state without the need for large scale involvement. (Beckley, 2017, p. 108)

The drawback of DbyD is that it seems unlikely to bring a conflict to termination. It may prevent the PRC from making gains, but this leaves a stalemate and leaves forces no way to break it except via escalation (toward blockade, an ASB or similar campaign or the nuclear variety). If the PRC can make gains, then DbyD alone cannot reverse these gains given it is tactically and operationally defensive. (Kearn, 2013, pp. 144-45) DbyD, is however not really a binary alternative to ASB. (Torsvoll, 2015, pp. 55-56) Krepinevich’s argument for ‘archipelagic defence’ is remarkably similar to Erickson and Gallagher’s proposed DbyD. Given Krepinevich’s place as an architect of ASB, DbyD is clearly compatible with ASB, and its incorporation into ASB would strengthen its deterrent value to a significant degree. (Krepinevich, 2015, pp. 80-83)

Of special note is the War-At-Sea concept of Kline and Hughes. Unlike proponents of Offshore Control and DbD, Kline and Hughes are supporters of ASB. This support is, however, conditional to the situation of an ‘all-out war’ with China. They propose war-at-sea as an intermediate state placed ‘Between Peace and the AirSea battle’ (the title of their Naval War College Journal piece). War-At-Sea avoids striking the Chinese mainland, and instead focuses on the use of mining Chinese ports and bases, utilising US submarine superiority to target the PLAN, and distant blockade. Due to its less escalatory nature, the authors argue War-At-Sea would be a better deterrent for medium scale aggression/provocations than an ASB campaign as the PRC would consider it more realistic and thus credible. (Kline & Hughes, 2012, pp. 33-37, 40)

Inevitability

Etzioni argues that the US assumes war with China as inevitable, and that this makes war more likely. He also argues ASB represents the Pentagon ‘planning for war with China’ without civil government restraint and thus the US military exceeding its authority and intruding into policy making. (Etzioni, 2014) (Etzioni, 2013)

This is perhaps the easiest argument to refute. States have, and should have contingency strategies for unexpected events, including wars with other major powers. The US military’s ‘war plan red’ of the 1930’s for war with generally friendly Britain (and its empire, including neighbouring Canada) was such a contingency plan, for a war that never occurred. (Ressa, 2010, pp. 54-56) Similarly, ALB and the Maritime strategy aimed to devise the best way to fight the USSR, a more likely adversary, but one that was also never fought. (Lock-Pullan, 2005, pp. 681-688) (Brooks, 1986, pp. 87-88)

Conversely, the Soviet Union in the cold war wrote its own doctrine, devised strategies and conducted exercises simulating fighting NATO, including the now infamous and nuclear heavy ‘Seven Days to the River Rhine’. (Rennie, 2005) It seems foolish to suggest that the PRC, given its disposition of forces and claims on Taiwan and the Senkaku islands has not conducted similar imagined campaigns in classified literature, especially given Christensen’s examination of Wang and Zhang’s (Chinese officers writing in PLA journals) explicit discussion of American resolve and sensitivity to casualties. (Christensen, 2001, pp. 17-20) (Defence Intelligence Agency, 2019, p. 8)

More subtly, ASB does not call for supremacy or dominance over China, but a preservation of a stable military balance in the WPTO, it is as concerned with deterrence as it is with warfighting. (Van Tol, et al., 2010, pp. 17, 29) Being prepared to fight the PRC is not the same thing as wanting to fight it; contingency planning and doctrine writing do not make war inevitable. ASB as a doctrine makes war with China no more likely than OfC or DbD.

Escalation and the Nuclear Question

ASB’s assumption that nuclear deterrence will hold is an understandably contested claim. Intrinsically linked to this is the criticism that ASB is unduly escalatory. (Etzioni, 2014, pp. 583-584) Conflict between two nuclear powers has the potential, however miniscule, to end in a nuclear exchange and the deaths of many millions. Talmadge frames the debate as between ‘optimists’ who assume deterrence holds and ‘pessimists’ who believe in a high risk of nuclear escalation. (Talmadge, 2017, p. 50)

ASB critics point to the doctrine’s calls for strikes upon adversary/PRC early warning systems, C2 network, submarines and ballistic missile launchers. These systems have conventional and nuclear utility, and the extent to which the PLA practices discrimination between nuclear and conventional networks is considered largely unknown. The ‘pessimist’ argument is that conventional war itself signals some failure of deterrence; and that PRC may mistake ASB-style attacks on conventional targets as a counterforce strike targeting its nuclear deterrent; or that an ASB campaign may accidentally destroy aspects of that deterrent. If the PRC believed that its nuclear forces were being targeted, it would face a ‘use it or lose it’ situation and thus may well consider breaching it’s professed no-first-use policy. (Talmadge, 2017, pp. 53-55) (Etzioni, 2014, p. 584) (Dian, 2016, pp. 252-254)

By contrast, the optimists point to China’s comparatively small number of weapons, strong central party/government control over them and the aforementioned no-first-use policy. These aspects suggest it is unlikely Chinese weapons would be used by rogue elements, or that the PRC would respond to conventional force with a nuclear strike. The optimists also argue that the Chinese leadership is aware of ASB's intent as a conventional doctrine, and that if the US wished to conduct a counterforce strike, it could do so far more effectively with its own superior nuclear arsenal than ASB style conventional strikes. Furthermore, much of the PRC arsenal is TEL (Transporter-Erector Launcher) based and thus mobile and concealable, enhancing its survivability. (Talmadge, 2017, pp. 51, 82-85) (Dobbins, et al., 2017, pp. 1, 9) Talmadge herself, while appearing aloof from the debate states the Chinese arsenal is survivable, even if parts may be vulnerable to accidental destruction by an ASB campaign. (Talmadge, 2017, pp. 51-57, 82-85)

Talmadge considers both the optimists and pessimists flawed in their arguments and assumptions. She argues the pessimists overestimate the threat to PRC nuclear forces, but that the optimists underplay what the American ability to potentially strike these forces would signal to the PRC in wartime. She points to the paranoia in the CCP leadership during the Sino-Soviet border conflict and the high readiness that nuclear forces were placed upon in that relatively minor dispute. (Talmadge, 2017, pp. 88-89) However, her statement that the PRC arsenal is survivable shifts her towards the optimist camp. Such a cautious optimism seems the best conclusion to draw regarding escalation.

OFC and DbD do avoid these risks; their claim to be less escalatory is certainly true. However, as Kearn highlights, escalation taken more generally has a value as a deterrent. (Kearn, 2013, p. 144) Just as the Maritime Strategy and ALB sought to make any NATO-Pact conflict protracted, global and not fought on Soviet terms, an ASB campaign would involve inflicting immediate and long-term significant costs upon China and attack its source of strength – its A2/AD network. (Lock-Pullan, 2005, pp. 681-688) (Brooks, 1986, pp. 87-88) (Department of Defense, 2012, pp. 17-27) OFC and DbD, because they are not escalatory, lack the same level of threat to inflict these costs upon China and thus lack the deterrent value of ASB. (Kearn, 2013, p. 144)

War between two nuclear armed states is a prospect that bears obvious risk of escalation, and such risk can never truly be eliminated. However, despite these concerns, it seems that the Chinese nuclear arsenal would not be placed at enough risk to necessitate a ‘use it or lose it’ situation, and that the much larger US arsenal would sufficiently deter usage in any other scenario. Nonetheless, ASB/JAM-GC should ensure that all efforts to avoid targeting of nuclear systems are made, and the question of how to separate PRC nuclear and conventional C2 and infrastructure is one requiring further investigation by western intelligence and academia alike. (Talmadge, 2017, pp. 54, 57) Escalation is also not inherently a bad thing – it has a deterrent value in that it makes clear there will be costs inflicted upon an adversary; that the US would fight on its term’s not the PRC’s – unlike OfC and DbD, which give the PRC space and time rather than inflicting immediate punishment and costs upon it. (Kearn, 2013, pp. 144-45)

Signalling, Resolve and Credibility

It is important to consider what ASB signals to the PRC. For ASB to deter effectively, this signalling must demonstrate the resolve to act in the way illustrated by the doctrine. If an adversary does not believe that a deterrent is credible, then it ceases to be so. Thus, the arguments above that escalation has a deterrent value break down if the PRC does not believe that the US would conduct a campaign based around ASB doctrine.

Based upon Christensen’s interpretation of Whang and Zhang, there appears to be a widespread assumption in the PRC that American resolve to bear casualties and other (economic and materiel) costs is low. (Christensen, 2001, pp. 10, 14-20) The reality is far more complicated. Scholarship suggests the US public is willing to suffer casualties in a war if they perceive the cause to be just and there seems a reasonable chance of victory. Jentleson illustrates how causes of ‘Foreign Policy Restraint’ – punishing an aggressor or breaker of international law are more generally supported over those of ‘Internal Political Change’ – replacing the government of an adversary. (Jentleson, 1992, pp. 53-54, 71-72). The issue then is getting the PRC leadership to believe that the US has the resolve to fight and suffer losses, for the deterrent value of ASB to be realised.

It is difficult to signal unity of purpose and willingness to sacrifice while maintaining freedom of speech and a free press, and such concerns are beyond the scope of this paper. Besides, such assumptions about the West by the Chinese leadership are probably deeply held and hard to change. However, resolve can be also be signalled through continuing existing actions that demonstrate intent to challenge provocative PRC behaviour, such as diplomatic and economic support for allies with land or maritime borders with the PRC, and regular FONOPS conducted by the US Navy. (Beckley, 2017, pp. 116-119) (Berkovsky, 2018, pp. 353-54)

The ASB/JAM-GC doctrine can be modified to demonstrate resolve. As stated previously, DbyD is not a binary alternative to ASB, it could and should be integrated into it. Similarly, including War-at-Sea within ASB as a response to small scale provocations short of a massive Chinese attack as imagined by van Tol is also achievable and prudent. This modified version of ASB/JAM-GC would be more credible due to the greater flexibility and control over escalation and contribute to ASB’s’ already strong deterrent value. (Krepinevich, 2015, pp. 80-84) (Kline & Hughes, 2012, pp. 33-37, 40)

Conclusions

This piece has examined ASB and related concepts in strategic thought and laid out the author's argument that AirSea battle is an effective deterrent to the PRC. In having an effective counter to Chinese A2/AD, the US and its allies preserve the stable military balance in East Asia that has kept the peace since the end of the Korean War; and its endorsement by American authorities demonstrate resolve to act and the technological and professional means to do so effectively if deterrence fails. In this unlikely but not implausible scenario, only ASB, unlike suggested alternatives allows the US to reverse the gains of an initial Chinese attack, inflict losses upon the PLA and threaten Chinese prosperity; thus making it the best option to bring said conflict to termination in favour of the USA as swiftly as possible.

ASB’s alternatives, as stated, are not really alternatives. ASB includes the distant blockade that is Offshore Control and combines it with immediate acting strikes and the restoration of manoeuvre and command of the commons. (Van Tol, et al., 2010, pp. 53-75) Deterrence by Denial, despite being articulated as an alternative is in fact perfectly compatible with ASB (as evidenced by the endorsement of Krepinevich) and would strengthen it as a deterrent. Given JAM-GC’s provision for involvement of land forces, this could be a niche filled by the US Army and/or Marine Corps. (Krepinevich, 2015, pp. 79-83) War-at-Sea could also be incorporated into ASB as an intermediate response to smaller scale attack or provocation, allowing for some control of escalation and applicability in a wider range of scenarios. (Kline & Hughes, 2012, p. 40) These so called ‘alternatives’ should be embraced by and subsumed into ASB, increasing its flexibility and deterrent value.

ASB is not without its drawbacks. As critics point out, there is the potential for escalation, something that cannot be taken lightly between two nuclear powers. Nuclear escalation cannot be discounted but does seem unlikely given the imbalance in the PRC and US weapon stockpiles, and the fact that even a highly successful US campaign would be unlikely to jeopardise the entire PRC nuclear force. (Talmadge, 2017, pp. 79-84) The escalatory nature of ASB too, is not inherently bad. It demonstrates resolve and willingness to take and inflict casualties, thus contributing to deterrence (by punishment). (Kearn, 2013, pp. 144-45) This is with the proviso of credibility – China must take seriously American intent to escalate (execute an ASB style campaign) for there to be any deterrent effect.

As an affordable, deterrent and conflict-suitable doctrine, ASB is well suited to managing a rising PRC. It is the best proposed way (yet) of overcoming Chinese asymmetric strategy that includes its substantial and potent A2/AD network and concepts of active defence and Shashoujian that are clearly targeted towards fighting the US. (Krepinevich, 2010, p. 15) (Defence Intelligence Agency, 2019, pp. 23-24, 53) ASB preserves crucial American access to the global commons and the stable regional military balance that prevents war. This value as a deterrent is tied to its (potential) war winning value. (Van Tol, et al., 2010)

For ASB to be as effective as possible in deterring and if needed, fighting the PRC, it seems prudent for the following measures to be considered and implemented. Some form of ‘allied ASB’ as proposed by Takahashi and Schreer should be created, with Australia and Japan having full access to the latest version of ASB/JAM-GC and input into implementation and further development, given their assumed participation. (Takahashi, 2012, pp. 1-9) (Schreer, 2013, p. 38) This is of benefit to the United States – it strengthens existing alliances, and potentially allows for a degree of burden-sharing and specialisation, as well as increasing the credibility by signalling that Australia and Japan are committed to ASB. This is particularly important in the case of Japan, with its key US bases and significant navy and air force. (Van Tol, et al., 2010, pp. 14, 20) (Ritter, 2005, pp. 240-248)

The Pentagon’s procurement efforts should include the acquisition/development of capabilities useful for ASB. As JAM-GC highlights, budgets are strained, especially given the ongoing economic impact of Covid-19. Thus, acquisition should avoid grand, concept/technology demonstrator stage projects like railguns, lasers, 6th gen aircraft, stealth ships and active space defences. Instead, such efforts should look to rebalancing existing forces, and off-the-shelf or easily developed systems/capabilities using the US’s established technological and industrial base.

(Hutchens, et al., 2017, pp. 4-6)

Numerous scholars point to the following as beneficial for ASB:

- Longer ranged anti-radiation, air-to-surface and ship-to-land missiles.

- ASW capabilities.

- Point defences (CIWS and ABM).

- AWACS aircraft and other redundant/alternative C2 systems to satellites.

- Hardening of air and (where possible) naval bases.

- Larger PGM stocks.

- Land based anti-ship artillery weapons for the Army and Marine Corps.

(Van Tol, et al., 2010) (Matsumura, 2014) (Dobbins, et al., 2017)

Perhaps most important for ASB to be effective is the effective signalling of American resolve to carry out an ASB style campaign. ASB will not deter if China believes it not to be credible. Critics note ASB’s massed strikes make it a drastic step to take, and one the PRC may not take seriously. By incorporating war-at-sea and DbD into ASB/JAM-GC, the doctrine gains credibility and flexibility.

As stated, the deterrence and combat effectiveness of ASB are inherently tied to each other. The US must demonstrate it is capable and willing to execute ASB to, paradoxically, lessen its chances of having to actually do so. (Van Tol, et al., 2010, p. 10) It may be something of a cliché, but si vis pacem, para bellum’, holds true in the present as it has in the past.

Select Bibliography (works cited)

Beckley, M., 2017. The Emerging Military Balance in East Asia: How China's neigbours can check Chinese military expansion. International Security, 42(2), pp. 78-119.

Berkovsky, A., 2018. US Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs) in the South China Sea: Able to Keep Chinese Territorial Expansionism. In: M. Clementi, M. Dian & B. Pisciotta, eds. US Foreign Policy in a Changing World. London and Berlin: Springer Nature, pp. 339-356.

Biddle, S. & Oelrich, I., 2016. Future Warfare in the Western Pacific. International Security, 41(1), pp. 7-48.

Bitzinger, R. A., 2016. The PLA Navy and the US Navy in the Asia-Pacific: Anti Access/Area Denial vs AirSea Battle. In: A. T. Tan, ed. Handbook of US-China Relations. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 398-410.

Bowers, I., 2018. Escalation at Sea:. Naval War College Review, 71(4), pp. 45-66.

Brodie, B., 1955. Some Notes on the Evolution of Air Doctrine. World Politics, 7(3), pp. 349-370.

Brooks, L. F., 1986. Naval Power and National Security: The Case for the Maritime Strategy. International Security, 11(2), pp. 58-88.

Brudzinski, J., 2004. Demystifying Shashoujian: China's Assassin's Mace Concept. In: A. Scobell & L. Wortzel, eds. Civil Military Change in China: Elites, Institutes, and Ideas ater the 16th Party Congress. Carlisle, Pennsylvania: Strategic Studies Institute: US Army War College, pp. 309-364.

Chapman, B., 2009. Military Doctrine: A Reference Handbook. 1st ed. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO.

Christensen, T., 2001. Posing problems without catching up: China's rise and challenges for US security policy.. International Security, 25(4), pp. 5-40.

Cliff, R. et al., 2007. Entering the Dragon's Lair: Chinese Anti-Access Strategies and thier Implications for the Unites States, Santa Monica: RAND Corporation.

Collins, G., 2018. A Maritime Oil Blockade Against China: Tactically Tempting but Strategically Flawed. Naval War College Review, 71(2), pp. 49-78.

Corbett, J. S., 1911. Some Principles of Maritime Strategy. 1st ed. London and New York: Longmans, Green and Company.

Davin, M. E., 2013. Anti Access/Area Denial: Time to Ditch the Bumper Sticker?, Newport, Rhode Island: United States Naval War College .

Davis, M., 2016. Future War: China and the United States. In: A. T. Tan, ed. Handbook of US-China Relations. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 430-447.

Defence Intelligence Agency, 2019. China Military Power: Modernising a Force to Fight and Win, Washington D.C.: Department of Defense.

Department of Defense, 2012. Joint Operational Access Concept (version 1), Washington D.C.: Department of Defense.

Dian, M., 2016. The Pivot to Asia, Air-Sea Battle and contested commons in the Asia-Pacific Region. The Pacific Review, 28(2), pp. 237-267.

Dobbins, J., 2012. War with China. Survival, 54(4), pp. 7-24.

Dobbins, J. et al., 2017. Conflict with China Revisited: Prospects, Consequences and Strategies for Deterrence, Santa Monica: RAND Corporation.

Dodds, K. & Sidaway, J. D., 2004. Halford Mackinder and the 'Geographical Pivot of History': A Centennial Retrospective. The Geographical Journal, 170(4), pp. 292-297.

Drew, D. M., 1995. Inventing a Doctrine Process. Airpower Journal, Issue 4.

Erickson, A., 2013. China’s Naval Modernization: Implications and Recommendations, Washington D.C.: House of Representatives Armed Services Committee (Seapower and Projection Forces Subcommittee) .

Etzioni, A., 2013. Who prepared for war with China?. Yale Journal of International Affairs, 8(2), pp. 37-51.

Etzioni, A., 2014. The Air-Sea Battle 'concept' : A critique. International Politics, 51(5), pp. 577-596.

Feng, H. & He, K., 2019. A dynamic strategic culture model and China’s behavior in the South China Sea. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, pp. 1-21.

Gallagher, M., 2019. State of (Deterrence by) Denial. The Washington Quarterly, 42(2), pp. 31-45.

Ghiselli, A., 2018. Revising China’s Strategic Culture: Contemporary Cherry Picking of Ancient Thought. The China Quarterly, pp. 166-185.

Gough, B. M., 1988. Maritime strategy: The legacies of Mahan and Corbett as philosphers of Sea power. The RUSI Journal, 133(4), pp. 55-62.

Greenert, J. & Schwartz, N., 2012. AirSea Battle. The America Interest, 20 02.

Guha, M., 2019. Shashoujian, or, the Way of the Dragon. The RUSI Journal, 164(3), pp. 38-50.

Hammes, T., 2012. Offshore Control: A proposed strategy. Infinity Journal, 2(2), pp. 10-15.

Hattendorf, J. B., 2014. The Idea of the Fleet-in-Being in Historical Perspective. Naval War College Review, 67(1), pp. 42-60.

Hutchens, M. et al., 2017. Joint Concept for Access and Maneuver in the Global Commons. Joint Forces Quarterly, 84(1), pp. 134-139.

Jentleson, B., 1992. The Pretty Prudent Public: Post Post-Vietnam American Opinion on the use of Military Force. International Studies Quarterly, pp. 49-74.

Jinn, G.-W., 2004. Chinese Asymmetric War and the Security of Taiwan, Montery, California: Naval Postgraduate School.

Kearn, D., 2013. Air-Sea Battle and China’s Anti-Access and. Orbis, Issue 4, pp. 132-146.

Kline, J. & Hughes, W., 2012. Between Peace and the Air-Sea Battle: A War-At-Sea. Naval War College Journal , 65(4), pp. 34-40.

Krepinevich, A., 2010. Why AirSea Battle, Washington D.C.: Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments.

Krepinevich, A., 2015. How to Deter China: The Case for Archipelagic Defense. Foreign Affairs, 94(2), pp. 78-86.

Krepinevich, A., Watts, B. & Work, R., 2003. Meeting the Anti-Access and Area Denial Challenge, Washington D.C.: Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments.

Lock-Pullan, R., 2005. How to rethink war: conceptual innovation and AirLand Battle. The Journal of Strategic Studies, 28(4), pp. 679-702.

Long, J. W., 1991. The evolution of US army doctrine: from active defence to AirLand Batte and Beyond, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: US Army Command and Staff College.

Lukin, A., 2015. Mackinder Revisited: Will China Establish Eurasian Empire 3.0?. The Diplomat, 7 February, pp. 1-4.

Mackinder, H. J., 1904. The Geographical Pivot of History. The Geographical Journal, 23(4), pp. 421-437.

Mahan, A. T., 1890. The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660-1783. 1st ed. New York: Little, Brown and Company.

Matsumura, M., 2014. The Limits and Implications of the Air Sea Battle Concept: A Japanese Perspective. Journal of Military and Strategic Studies , 15(3), pp. 23-59.

Mehta, A., 2018. The US is running out of bombs — and it may soon struggle to make more. DefenseNews, 22 May.

Mirski, S., 2013. Stranglehold: The Context, Conduct and Consequences of an American Naval Blockade of China. Journal of Strategic Studies, 36(3), pp. 385-421.

Moore, L., 2014. China's Antisatellite Program: Blocking the Assassin's Mace. Asian Perspective, 38(1), pp. 163-178.

Mowbray, J. A., 1995. Air Force Doctrine Problems 1926-Present. Air and Space Power Journal, Volume 155, pp. 2-17.

Murphy, M., 2015. Kick the Door Down with AirSea Battle… Then What?. Parameters, 45(2), pp. 97-109.

Peifer, D. C., 2011. China, the German Analogy, and the new AirSea battle operational concept. Orbis, Issue 4, pp. 114-131.

Posen, B., 2003. Command of the Commons: The Military Foundation of US hegemony. International Security, 28(1), pp. 5-46.

Prescott, M., 2016. Corbett and Air-Sea Battle: How the Joint Force can Maintain Access using the “Fleet in Being” Concept. Army Press Online Journal, 16(18), pp. 1-7.

Reeve, J., 2000. The Development of Naval Strategy in the Asia Pacific Region 1500-2000, Canberra: Royal Australian Navy Sea Power Centre.

Rennie, D., 2005. World War Three seen through Soviet eyes. The Daily Telegraph, 26 November.

Ressa, K. T., 2010. US vs the world: America's color coded war plans and the evolution of rainbow five, Lynchburg, Virginia: Liberty University.

Ritter, T., 2005. The Regional Command of the Commons: Japan's Military Power. Korean Journal of Defence Analysis, 17(1), pp. 235-258.

Røksund, A., 2007. The Jeune Ecole: The Strategy of the Weak. 1st ed. Leiden: Brill.

Schmidt, S. D., 1993. A Call for an Official Naval Doctrine. Naval War College Review, 46(1), pp. 45-58.

Schreer, B., 2013. Planning the unthinkable war: AirSea Battle and its implications for Australia, Canberra: Australian Strategic Policy Instiutute .

Takahashi, S., 2012. Counter A2/AD in Japan-U.S. Defense Cooperation: Toward 'Allied Air-Sea Battle'. Futuregram, 12(3), pp. 1-9.

Talmadge, C., 2017. Would China go nuclear? Assessing the Risk of Chinese Nuclear Escalation in a Conventional War with the United States. International Security, 41(4), pp. 50-92.

Till, G., 2009. Seapower: A guide for the 21st Century. 2nd ed. Abingdon: Routledge.

Torsvoll, E., 2015. Deterring Conflict with China: A comparison of the Air-Sea Battle concept, Offshore control and deterrence by denial. Fletcher Forum of World Affairs, 39(1), pp. 35-62.

Tritten, J. J., 1994. Naval Perspectives for Military Doctrine Development, Norfolk: United States Navy.

Tritten, J. J., 1995. Naval Perspectives on Military Doctrine. Naval War College Review, 48(2), pp. 22-38.

Van Tol, J., Gunzinger, M., Kripinevich, A. & Thomas, J., 2010. AirSea Battle: A Point of Departure Operational Concept, Washington D.C.: Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments.

Wexler, K., 2020. The Power of Politics: How Right-Wing Political Parties Shifted Japanese Strategic Culture, Boulder, Colorado: University of Colorado, Boulder .