22 January 2021

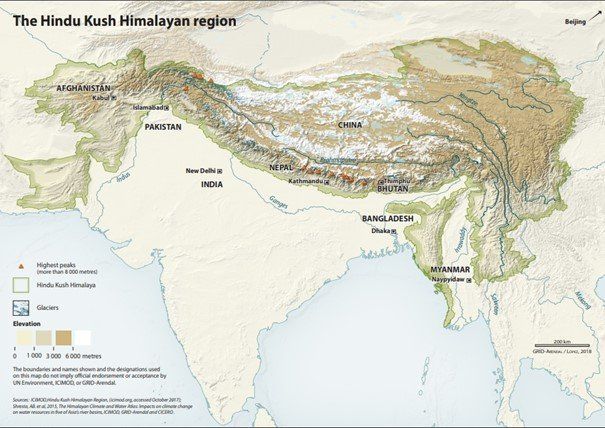

The sources of the Indus River can be traced high into the mountainous regions of the Himalaya and the Hindu Kush. Conflict in this region is nothing new, it is written into the very landscape itself, with the name of the mountain chain Hindu Kush translating to the killer of “Hindus” or “Indians” in Persian. Yet, Climate Change, population growth and economic development, all threaten to increase tensions in the region, as pressure on the already overutilized Indus river and its tributaries slowly grow beyond a sustainable threshold.

^ Source: GRID-Arendal

After this initial conflict in Kashmir ended, the parties agreed to a UN-mediated ceasefire along a Line of Control, giving India control of roughly 45% of Kashmir and Jammu along with 70% of its population. In comparison, Pakistan controls 35% of the northern region. The remaining 20% belongs to the Chinese province of Aksai Chin in the autonomous province of Tibet. Although neither party was completely satisfied with the Line of Control, it has remained relatively static in the subsequent conflicts apart from Pakistan ceding territory in the North to China in 1963, and India seizing control of the Siachen Glacier in 1984.

This presents Pakistan with a serious problem. The five main tributaries that supply water to the Indus river either originate in or travel through territory occupied and claimed by India. This includes the Jhelum the largest of the tributaries that originate in Kashmir and the Chenab, which flows through the Jammu territory before entering the Indian region of Punjab. The other three tributaries the Ravi, Sutlej and Beas also originate in or flow through the Indian state of Punjab before entering Pakistan. This means that India is currently the main upper riparian and holds a serious advantage when it comes to the management of the water level in the Indus river. This is especially problematic for Pakistan since the Indus is the only reliable large water source and the nation is 92% arid and semi-arid.

The wider international community realized this unfortunate situation and to avoid further conflict over water scarcity a settlement was negotiated by the World Bank in 1960. The Indus Water Treaty (IWT) as it would be known, granted India exclusive access to the east-flowing rivers of Sutlej, Ravi and Beas which represents roughly 33 million-acre-feet (MAF) of water. Pakistan, on the other hand, received exclusive rights to the western flowing Indus, Jhelum and Chenab, which amounts to roughly 135 MAF. In contrast, India received only limited access to these rivers and was not allowed to undertake any activity that would limit the water in these rivers from reaching Pakistan.

This settlement has largely been successful with the IWT being heralded by many as a good example of water diplomacy. The treaty even survived the subsequent conflicts waged between India and Pakistan and remained one of the few areas that saw continued cooperation during the 1999 conflict over Kargil. However, several issues ranging from population growth to pollution and Climate Change, are now plaguing the 80 years old treaty and threatening the status quo.

Starting with waterflow, the Indus is one of the world's largest rivers if measured by the annual flow of water. At 243km³ its yearly flow is twice that of the Nile and three times that of the Euphrates and Tigris river combined. Around 80% of the water in the Indus is derived from meltwater coming from glaciers located in the Himalayas, and the remaining is supplied through natural springs and rain. Yet despite this massive inflow of water it only reaches its end in the Arabic Sea 2 months of the year, during the Monsoon season, the rest of the year it dries up before reaching the sea. This is mainly due to the immense amounts of water required for agriculture, the redirecting of water through canals and the storage of water in reservoirs for hydroelectric power.

Irrigation remains the largest consumer of water, representing 93% of all water removed from the river. The Indus is relied upon to water more than 90% of the agricultural area in Pakistan, and it provides water for a third of the rice stock and half of the wheat stocks distributed through the Indian Public Distribution System, thus forming a critical part in India’s national food security network. The importance of the Indus on the region’s agriculture has led to some calling the Indus basin the breadbasket of the subcontinent. Agriculture further employs 39 percent of the Pakistani labour force and generates 18.5% of its Gross National Product (GDP) in 2018. Making the river essential for the survival of the Pakistani state.

Hydroelectric power also takes up considerable amounts of water from the Indus and its tributaries. Although hydropower build-up in India and Pakistan pales in comparison to their regional neighbour China, it is still responsible for considerable conflict between them. The first significant dispute requiring international mediation under the IWT was in 2005 when India went forward with its planned 450-megawatt Baglihar hydropower project on the Chenab. Although this river was granted to Pakistan in the IWT, the treaty allowed India to use the waters in the western rivers in a non-consumptive manner. India claimed the Baglihar dam would have no effect on waterflow to Pakistan, a claim that Islamabad hotly refuted. The situation was only settled when international mediators negotiated corrections in the dam design, including a smaller water reservoir. Despite this temporary solution politicians and pundits in Islamabad repeatedly claim that India is misusing its position as upper riparian to keep water from reaching Pakistan. They claim that although the Indian dams on the rivers align with the IWT, their cumulative effect is a loss of waterflow. This cumulative argument is something the IWT did not focus on as it did not call for a systematic aggregate impact assessment, and as a result, it represents a severe point of friction.

The security implication of these dams is serious for Pakistan. Even if India does not dam the river enough to cause a loss of waterflow, the barriers certainly give them the ability to do so. As the waterflow of the Indus is critical for Pakistan’s agriculture, the dams also give India the ability to interrupt or increase waterflow at crucial periods of the year, causing losses in agricultural output and potential famine in Pakistan. These risks are not lost on the policymakers in Islamabad, and they are not necessarily unfounded. In 2008 when the Indian government decided to fill the Baglihar reservoir, it coincided with a critical period of drought and negatively impacted Pakistani farmland according to John Briscoe a Hydrologist at Harvard University. These events have caused several radical groups within Pakistan, such as the Al-Qaeda linked group Jamaat-ud-Dawa, to call for a war on India to reclaim water rights. Other militant groups such as the Lashkar-e-Taiba responsible for the deadly 2008 Mumbai attack, have even threatened to attack Indian water infrastructure in Kashmir.

Suppose water scarcity was to increase in the region. In that case, there is little to stop Pakistan from deploying these armed militant groups into Kashmir to destabilize the region and cripple Indian infrastructure. However, as upper riparian India holds another trump card, namely that of gravity. If Pakistan or violent extremists were to cripple several Indian dams the cascading water would cause a significant flood further down likely harming Pakistan in the process.

^ Source: GRID-Arendal

The multiplying factor of population growth further complicates the issues of energy, food and water security. Since the IWT was signed in 1960, the Indus region's population has ballooned to 276 million people. By some estimates that number is set to nearly double to 346-469 million by 2050. Regional GDP will also grow by a factor of anywhere from four to eight times. These developments are putting a serious strain on the already overutilized Indus and are threatening the IWT as it makes no provisions for increasing populations.

These demographic changes are having a serious effect on water scarcity. As noted by Adil Khan and Nazakat Awan: “A snapshot of per capita availability of water at the time of independence and in the year 2017 better explains this disequilibrium. At the time of independence (in Pakistan) per capita availability of water was 5000m3 whereas, this volume shrunk to only 1000m3 presently”. Per capita water availability will only grow worse with the increasing population and the required increase in agriculture, that a larger population requires.

Climate Change is another potential multiplying factor adding to the problems in the Indus basin. As most water in the Indus river comes from Himalayan glaciers, the river is highly susceptible to any change in annual meltwater. Estimates vary, but it is safe to assume that higher global temperatures will have an adverse effect on the amount of annual meltwater. The annual flow of water in the Indus will likely increase due to deglaciation, before sharply declining as Climate Change melt the Himalayan Glaciers.

The further effects of Climate Change on the region are largely unclear. Still, analysts predict that increasing temperatures could affect the local climate, even changing cloud patterns and precipitation. Different models calculate the effects differently, but water availability in the Upper Indus region could increase by 60% or fall by 15% by 2100. Although Climate Change's full impact is unclear, when coupled with increased population and industrialization it is highly likely to increase per capita water scarcity.

Increased per capita water scarcity will likely cause increased interstate conflict between India and Pakistan, but it can also cause intrastate conflict. The state of Sindh and the state of Punjab in Pakistan already have a history of water disputes, and the unstable political system in Pakistan will come under increased internal pressure as water becomes scarcer. Furthermore, the state of Jammu & Kashmir in India is also facing internal unrest due to the conflict between the pro-Hindu Indian government and the majority Muslim population. If water were to become a limited resource in the state, it would provide further fuel to fire up local tensions.

Finally, there are two other nations in the region. Both Afghanistan and China have so far remained relatively inactive on the Indus river issues, but that might change in the future. Afghanistan is in dire need of development and damming rivers to provide the government and people access to energy could help stabilise the nation. Furthermore, China has not dammed the Indus or tributaries near their sources in the Tibetan plateau, largely due to the remote nature of these springs. Still, with water becoming an ever more precious resource, China might move to secure their right as a riparian state. This latter scenario is highly likely if India and China escalate their geopolitical power struggle in the region. China is not afraid of protecting its rights in the region, as was shown in the bloody border conflict in the Galwan Valley in June 2020, where at least 20 Indian troops died, and damming the river would send a powerful message to New Delhi.

The Indus and its tributaries are facing mounting pressure from Climate Change, increased population growth and industrialization. To alleviate some of the pressure Pakistan and India need to cooperate in accurate monitoring and gathering of water data, which has seen little cooperation until now. Furthermore, both nations need to invest in more efficient agriculture to lessen the strain on the rivers. These steps require collaboration between the two powers and should be pursued by both nations. The alternative, complete devastation of the Indus River and its tributaries and subsequent conflict between the two states are in neither nation’s interests. As India and Pakistan are nuclear-armed nations a conflict over water in Kashmir would be a very dangerous game. The threats posed by Climate Change will hopefully move the nations closer to cooperation, for as Prime Minister of India Narendra Modi stated in 2016, “Blood and Water cannot flow together”.